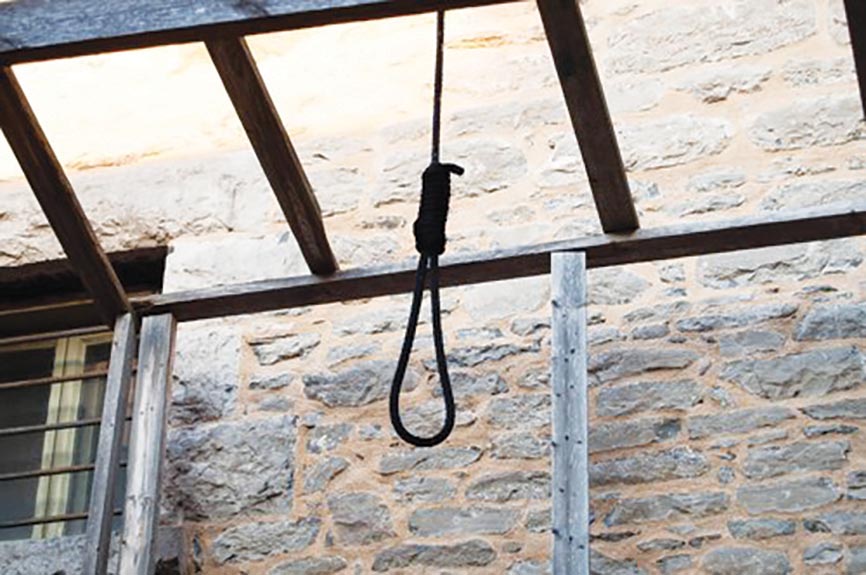

Penrith settlement began in the Castlereagh area along the Nepean River, but the Hawkesbury area was already settled. In September 1808, Hugh Dowling was on trial before A Bell, Esquire for armed burglary at the Hawksbury, stealing cash and clothing from the dwelling house of William Styles. Hugh was brought before the court on a charge of being in company with several other people who broke the front door and entered William Styles’ house and inhumanly beating and wounding James Seal who was sleeping in the house. From the testimony of William, his wife and James, it appeared that three people entered the house, leaving several others outside. It was decided that James getting out of his hammock in the outer room was easy to knock down and secured and then they went into the room where William and his wife slept. One of the party whose face was covered presented a musket at William’s breast and commanded them both to be silent while they ransacked the place saying that they were bushrangers and insisted on having everything they wanted, and they took bills to the amount of about £15 and all William’s wearing apparel and demanded his watch saying they would find it very useful. They then stopped to smoke a quantity of tobacco and made off taking all of James Seal’s wearing apparel. With much suspicion against the prisoner, he was fully committed to the county gaol for trial. In the Court of Criminal Jurisdiction Hugh was indicted for burglary, entering the dwelling house of William at the Nepean on the night of Tuesday the 13th of September and stealing a considerable property of money and wearing apparel, including the items of clothing his wife was sewing for Simeon Lord. In support of the charge, William said that between the hours of 11 pm and 12 pm his front door was violently burst open and soon after two men entered the inner room where his family laid, and as he got out of bed on hearing the noise they pointed a musket and threatened to kill him if he did not immediately return to bed and remain quiet, and his hands were bound by the prisoner. William swore positively that it was the prisoner, saying that he wore a cap over the upper part of his face and he had a clear opportunity of observing him as one of his accomplices held a lighted candle in his hand while the prisoner was examining one by one a number of notes that he took out of the pocket book and by doing this he had removed the cap sufficiently to give William a perfect view of his countenance. With the prisoner holding the contents of the book in one hand and the musket in the other he asked him several questions. They declared they were poor fellows in the bush who wanted some provisions and a little money and that they were determined to have it, and after ransacking the apartment they went out, but the prisoner returned shortly after saying “I’ll thank you for the loan of your watch”; but his wife told them that it could not be of any use to them as it was well known to many people in Sydney, so the prisoner replied “I ask your pardon madam” and the watch was given back and the prisoner again quitted the room and later returned again requesting the loan of a pipe and was told that two were on a shelf and he took one saying “I have taken one and left you one.” The prisoner then told William that they might thank themselves for being robbed and that if he offered to make any alarm they would return and be revenged. Afterwards they remained at the door smoking tobacco for nearly an hour and then went leaving an unfortunate family with their severe loss. James Seal who lived in the house said that upon the door being burst open he leapt from his hammock that was in the front room and was immediately knocked down and severely beaten and he was then compelled to return to his bed where he lay while the plunderers were employed on rummaging the house. They lit a fire, but his hammock was hanging high, and he dared not look downwards and could not identify any of the people. His personal chest was broken open and robbed. The testimony given by the wife of William was clear and conclusive. She swore positively that the prisoner at the bar was the man who tied one of her hands and was proceeding to bind the other one but desisted upon her remonstrating against the inhumanity of the act, as she had an infant at her breast. It seemed that the witness had a strong and perfect recollection of the prisoners features, having observed him attentively examining the notes with the cap pushed from his face and she was still more positive in the identity of his person because he had taken from her husband’s pocket book one note which he considered to be of no value to him and saying when he gave it to her “here is the book with the note in, take care of it.” She said that he had been in the house on the day before the robbery and was passing by the house the day after it, where he was challenged by her husband as the chief actor in the outrage. The whole of her testimony strictly coincided with that given by her husband and she entertained not the slightest shadow of a doubt with respect to the person of the prisoner. She pathetically remonstrated the distress which the barbarous outrage had entailed upon her unhappy family as they had been inhumanly deprived of every article of comfort and of every common necessary as her poor children were left in a state of nakedness, eating only mushrooms and Indian Corn their only food and unhappily they remain a prey to the calamities of real want. Hugh had set up an alibi that was contradictory in its most material point which carried with it every other mark of fabrication. Upon testimony so strong, so clear and so conclusive the Court of Criminal Jurisdiction found the prisoner Hugh Dowling guilty and to be hanged. In October 1808 Hugh was recalled to the bar to receive sentence of condemnation which was accompanied with a pathetic exhortation from the Acting Judge Advocate and on Thursday the awful sentence was carried into execution. (PS: The Court of Criminal Jurisdiction was a criminal court established in 1787 under the auspices of the First Charter of Justice in the British Empire of New South Wales and was the first criminal court in the colony).

Sources: Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser Sunday 25 September 1808 & Sunday 2 October 1808, Trove, Australian Biographical Database online.